Cranwell

CRANWELL : Military aerodrome (Also known as CRANWELL South & HMS DAEDALUS)

Note: Both these pictures (2010) were obtained from Google Earth ©

Notes: All pictures by the author unless specified.

Operated by: 2001: MoD for Royal Air Force

Military users: WW1: RFC/RAF RNAS Aeroplane School (Avro 504E)

RFC/RAF Training Depot Station Aircraft Repair Depot

RAF from 1919: RAF Central School of Flying (Avro 504K)

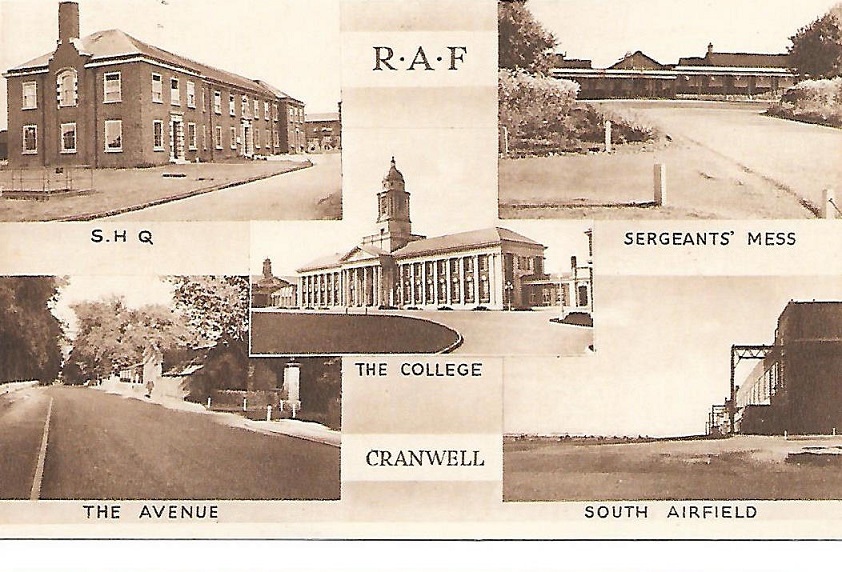

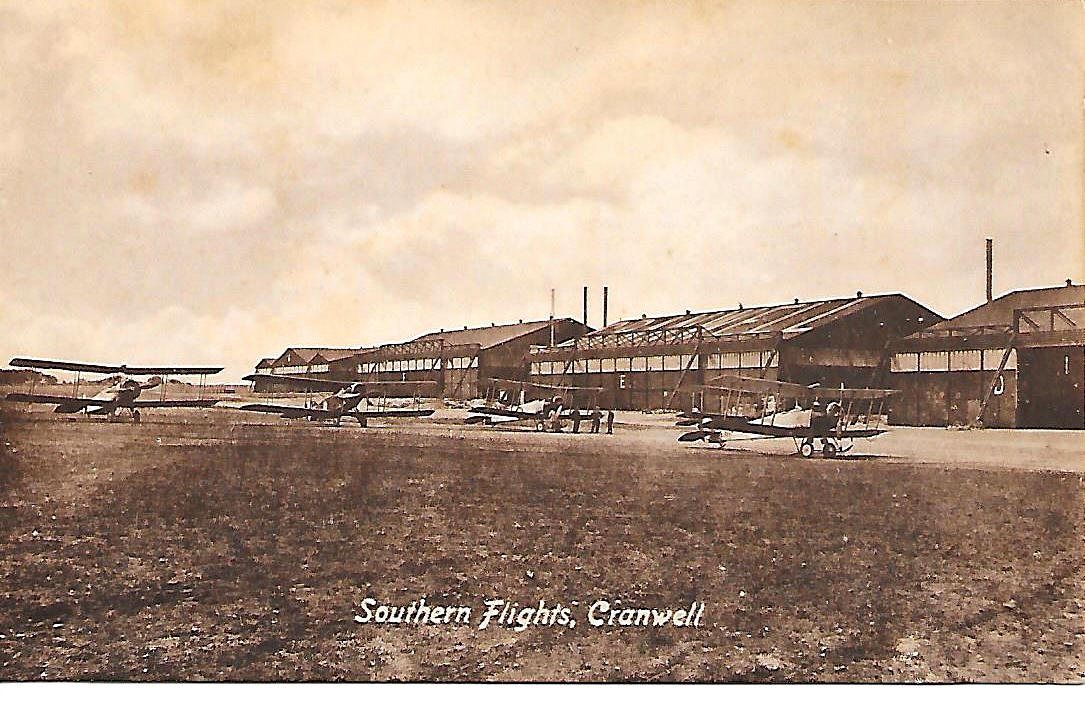

Note: In 2017 I was kindly contacted by Mike Charlton who has an amazing collection of British aviation postcards. www.aviationpostcard.co.uk

He sent me these two lovely sepia toned pictures, from postcards. Can anybody kindly date them? Regarding the second picture I imagine this was taken in the 1920s, probably early 1920s? Three of the aircraft appear to be Avro 504 types, (probably 504Ks?), but the second from the left appears to be a Bristol F2b Fighter?

Between the wars: RAF Central School of Flying (Armstrong-Whitworth Atlas, Avro 504K, Avro Tutors, Bristol F.2B Fighters, Bristol Bulldogs, Hawker Harts and Furys)

WW2: RAF Central School of Flying

1 RS 3 (Coastal) OTU (Bristol Beauforts, Vickers Wellingtons & Armstrong-Whitworth Whitleys)

Post 1945: RAF Central School of Flying

3 FTS (Hunting-Percival Jet Provosts)

45(R) and 55(R) Squadrons

Red Arrows display team

'V' Bomber dispersal airfield

1975: RAF Central School of Flying (Hunting-Percival Jet Provosts)

CEW (Hawker Hunters, SEPCAT Jaguars, Westland Whirlwinds)

1998 snapshot: RAF Operational Conversion Units

45 (R) Sqdn (3 FTS/METS) 10 x Jetstream T 1

55 (R) Sqdn (3 FTS) 8 x Dominie T 1 (mod)

2012: RAF initial basic training operated by Babcock International including the East Midlands Universities Air Squadron Grob 115 Tutors (The EMUAS scheduled to move to RAF WITTERING (NORTHAMPTONSHIRE) in 2014)

Beech King Air’s operated by 3FTS

Aero club: Pre 1940: Cranwell Light Aeroplane Club

Flying club: RAF College Flying Club (Dates?)

Location: S of B1429, N of A17, roughly 2nm WSW of Cranwell, 4nm NW of Sleaford, 9 nm NE of Grantham

Period of operation: 1916 to present day

Site area: (North and South) WW1: 2466 acres 3840 x 2560

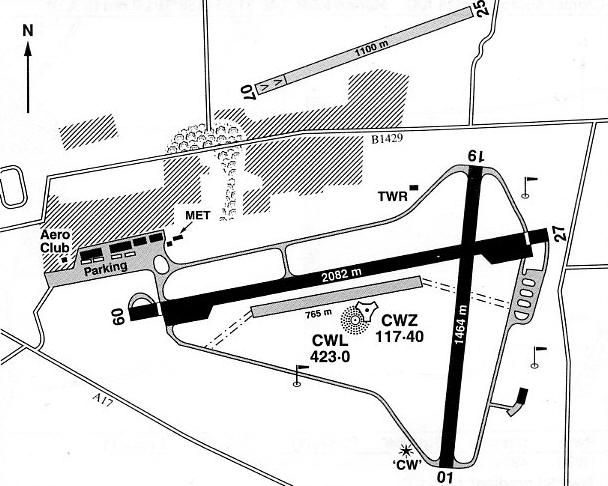

Note: This map is reproduced with the kind permission of Pooleys Flight Equipment Ltd. Copyright Robert Pooley 2014.

Runways: Originally ‘all over’ grass airfield(?)

WW2: N/S 1097 grass NE/SW 1371 grass E/W 822 grass

SE/NW 685 grass

1990/2000: 09/27 2082x46 hard 01/19 1464x46 hard

Grass runway parallel to and south of 09/27 listed as 765mtrs (no width given)

CRANWELL GALLERY In 2018

NOTES: The Royal Air Force was established on the 1st April 1918 and it combined the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service. However, when WW1 ended it had around two hundred and eighty squadrons operational but the political climate reflecting the attitude of the general public resulted in this force being swiftly reduced to just thirty squadrons – with much of the British Empire still to defend!

Patrick Bishop in his excellent book Wings does a great job of explaining the intrigues of this era and how the newly formed Royal Air Force had a struggle just to survive. In the end of it all, although not a fan of the Royal Air Force concept initially, ‘Boom’ Trenchard was appointed to run the struggling service and he had very definite ideas as to how its future would be determined, not least the concept that it would be entirely independent of the army and navy.

To quote from Partrick Bishop: “The army and navy had offered the use of their facilities to train up volunteers. Trenchard spurned them. The RAF would have its own colleges in which to inculcate the ‘air spirit’. Cranwell in Lincolnshire for the officer cadets; Halton in Buckinghamshire for the apprentices. Cranwell had been an RNAS station during the war and it was plonked on flat, wind-scoured lands in the middle of nowhere.” (My note: It still is!) “This, in Trenchard’s eyes, was one of its main attractions. He told his biographer that he hoped that ‘marooned in the wilderness, cut off from pastimes they could not organize for themselves, they would find life cheaper, healthier and more wholesome’.”

“This, he hoped, would give them ‘less cause to envy their contemporaries at Sandhurst or Dartmouth and acquire any kind of inferiority complex’. Some experts maintain the RAF (Cadet) College was founded here in December 1919 and this seems to be the case because: “In February 1920 RAF Cranwell was transformed into the Royal Air Force College. It was a grand name for a dismal, utilitarian cantonment. One of the first intake of fifty-two cadets described a ‘scene of grey corrugated iron and large open spaces whose immensity seemed limitless in the sea of damp fog which surrounded the camp’.

“They lived in single-storey huts, scattered on either side of the Sleaford Road, connected by walkways to keep out the rain and snow borne in on the east wind.” I cannot blame Patrick Bishop for employing such terms, all writers like to create a lasting impression, but from spring to autumn CRANWELL can often by quite idyllic – rural England at its best. I know because I have been there, several times. However, I can easily understand how this rural idyll would have held few attractions for most of the young men stranded there.

THE GENTLEMAN OFFICER

Despite the very basic accommodation in the early days, the idea was to recruit ‘gentlemen’ to become officers, or, on paper at least – to create ‘gentlemen’ from the recruits. As Patrick Bishop points out: “The RAF wanted boys who exhibited ‘the quality of a gentleman’. It was careful, though, to emphasize that by this it meant ‘not a particular degree of wealth or a particular social position but a certain character’. Ordinary boys from ordinary families were nonetheless unlikely to find the gates of Cranwell flung open to them. Air Ministry officials set out to recruit people like themselves, writing to the headmasters of their old schools, selling the college’s virtues, playing down the perils of air-force life and seeking candidates. Eton for example had a dedicated liaison officer.”

A LESSON NOT LEARNT?

This strikes me as very interesting, not least because the lessons learnt in combat during WW1 seemed to have been conveniently forgotten – and this is that the sort of person who makes a first class military pilot cannot be decided by class and social standing. Instead they used practicalities to make pretty certain that the vast majority of recruits came from the upper social strata of society and once again, Patrick Bishop gives a good example: “Unlike the public schools, few state schools had the resources to provide coaching for the entrance exam. Fees were steep. Parents were expected to pay up to £75 a year, plus £35 before entry and £30 at the start of the second year towards uniform and books. This was at a time when a bank manager earned £500 a year.”

“There was a backdoor route to Cranwell. It led from Halton, (My note: See HALTON, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE, where the RAF Technical School had been established), where every year the three best apprentices were offered a cadetship to the college with the expectation, frequently fulfilled, that this would lead them to the highest reaches of the service.” What Mr Bishop does not divulge however is how many of these successful Halton apprentices became first class pilots? Perhaps they all did but in my experience only the minority of aircraft engineers and technicians show any interest in flying. Indeed, as often as not when asked, the response has been along the lines of; “You must be joking, we know how the bloody things are made and maintained.” But of course by the 1980s and beyond the allure of actually flying an aeroplane had, for the general public, mostly dissipated although their appetite to attend airshows has, if anything it appears, increased.

Also, to further complicate the picture, (but not intentionally of course), Patrick Bishop also tells us: “In 1921 a new class of airman pilot was announced that offered flying training to outstanding candidates from the ranks. They served for five years before returning to their own trades, but retained the sergeants stripes they gained for being in the air. This policy meant that by the time the next war started about a quarter of the pilots in RAF squadrons were NCOs – a tough, skilful, hard-to-impress elite within an elite.” Under Trenchard’s watch a system of short-service commissions was introduced in 1924 and in 1925 the Auxiliary Air Force was formed. Both of these schemes proved to be of immense value when WW2 was declared, but, the fact remains that the RAF was mostly very ill-equipped and skilled to fully resist the Luftwaffe onslaught. Trenchard was of course relinguished of his post in 1930.

ANOTHER MYTH

Even today it is often claimed that the RAF were woefully unprepared when Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declared we were declaring war with Germany. This is far too much of a generalisation. Bomber Command had aircraft and crews which compared really very well with the Luftwaffe, but lacked numbers of aircraft and combat experience. Also RAF training techniques were pitiful for bomber crews. This didn't change until the RAF had been equipped with heavy four-engine bombers supplied in huge numbers, the arrival of radio navigation aids, and instructors who had been in combat. Coastal Command faired little better until supplied with Short Sunderlands and Catalinas and Liberators built by Consolidated in the USA.

However, Fighter Command was, by 1939 in a remarkably fit state to resist the Luftwaffe and the threat of an invasion, (which of course was never actually a possibility), as some far-sighted people had ensured we had some very capable fighters available - mostly the Hurricane but also the Spitfire. As the war progressed in the early stages both types had to be quickly modified to become more effective, and the woeful combat tactics taught adjusted for reality.

BACK TO CRANWELL

Getting back to Cranwell it now seems to me that the design of the main building was an inspired choice. It featured so often in the classic mostly black and white war films I saw as a lad, and (not that I considered such aspects), seemed timeless. In fact it was built in or around 1929. From Patrick Bishop again: “The design was inspired by Sir Christopher Wren’s Royal Hospital in Cheslea, and the brick and stone and classical proportions helped create an instant sense of tradition.” It really does and having stood there, at the main gate looking at it, it really is most convincing.

CRANWELL NOTES

In the 1920s the Cranwell Light Aeroplane Club built a series of aeroplanes, (Cranwell C.L.A.2 to C.L.A.4A types), mainly (?) to participate in the 1924 to 1926 Lympe trials.

20th May 1927. A modified Hawker Horsley day bomber J8607 flown by Flt Lt C. Roderick Carr and Flt Lt L. E. M. Gillman took off to attempt the first non-stop flight to India, and in doing so break the non-stop World Distance Record. It was forced down in the Persian Gulf after covering 3420 miles in 34.5 hours. But, despite the sad ending, they did indeed just break the World Non-stop distance record of 3,345 miles set by two French pilots the year before.

On the 13th March 1929 the Hon. Elsie Mackay and Capt Hinchliffe departed at 08.35 in a Stinson Detroiter to fly the Atlantic east to west. The flying career of Capt. Hinchliffe makes for fascinating reading, an almost legendary pilot. Both were lost without trace but, as so often happens, strange stories emerged later. Such as the elderly lady in Surrey receiving a psychic message on the 31st March 1929 saying, “I DROWNED WITH ELSIE MACKAY. FOG. STORMS. WIND. WENT DOWN FROM GREAT HEIGHT OFF LEEWARD ISLANDS”. On the other hand a Mr George Dean of Flint reports finding a small slightly damaged smelling salts bottle washed up on the estuary foreshore between Flint and Bagillt containing a tightly rolled slip of paper with the message still discernable, “Good-bye all. Elsie Mackay and Capt. Hinchliffe. Down in fog and storm”. Although handed in to the police this ‘evidence’ was, it seems, regarded as a cruel joke! No attempt it would seem was made to compare this hand-written note with other examples of her handwriting! Thanks be that we now have the AAIB today, and this sort of evidence would surely be thoroughly investigated, slim though it is?

MORE REMARKABLE FLIGHTS

24th April 1929. First successful non-stop flight to India from the UK departed here, taking 50hrs & 37mins in the Fairey Long-range Monoplane J9479.

27th October 1931. Ist non-stop flight to Egypt from the UK arriving the next day. Using the Fairey Long-range Monoplane K1991.

Note: In the early to mid 1930s Armstrong Whitworth ‘dual control’ Atlas types were employed here for flying training.

On the 6th Feb 1933 the Fairey Long-range Monoplane K1991 took off to fly to South Africa, landing at Walvis Bay. Piloted by Sgn Ldr O R Gaylord with Flt Lt G E Nicholetts as navigator it was the first non-stop flight over this 5,310 mile route. Arriving on the 8th having flown non-stop for 57 hours 25 minutes, thereby averaging about 93mph over the ground! Walvis Bay, in Namibia on the west cost of South Africa is not an obvious destination, so why land there? Perhaps a combination of fuel and crew exhaustion?

AN EXPLANATION

Asked to explain why the RAF were intent on world record breaking long distance flights such as this, the Air Ministry answer was; “Our Empire is large but the Air Force is small and therefore must compensate with greater mobility.” Hardly a surprise, the public were being fed bullshit then, and we still are! So ten out of ten for consistency.

THE JET ERA

Regarding the development of jet aircraft in WW2 it seems reasonable to suppose that a ‘centre of excellence’ might have been established? Certainly for test flying – and at first this seems to have been here. You really might think that today the date and place for such an event as the first flight of a British jet aircraft would be beyond dispute, but it isn’t. Some experts claim the Gloster E.28/39 first flew here on the 15th March 1941 while others state the 15th May. For what it’s worth Wikepedia also support the claim the E.28/39 first flew here on the 15th May 1941 flown by Gloster’s chief test pilot Gerry Sayer, a flight lasting seventeen minutes. Perhaps I should also mention that some accounts claim that this first flight was from CRANFIELD (BEDFORDSHIRE) and, I now firmly believe that this is the case.

AN ANSWER?

It now appears that the first flights of the Gloster E.28/39 were from the Gloster companies grass airfield at BROCKWORTH (GLOUCESTERSHIRE). Flight testing being transferred here because the airfield had a much longer runway.

MORE INFO

Quoting Robert Jackson: “Within days the aircraft was reaching speeds of up to 370 mph at 25,000 feet, with the engine set at 17,000 rpm, exceeding the performance of contemporary Spitfires. Two E.28/39s were built, the first being W4041/G, but the second aircraft, W4046, was destroyed on 30 July 1943 when its ailerons jammed and it entered an inverted spin. The pilot, Squadron Leader Douglas Davie, baled out at 33,000 feet (10,065 m), the first pilot to do so from a jet aircraft.” Perhaps this account should now be re-examined as surviving a bale out from 33,000 feet without modern protective clothing, or oxygen etc, seems a tad unlikely? This said, it seems he did suffer from frostbite on the way down. It seems to me that having achieved 33,000ft and then finding himself in an inverted spin, Davie would probably have spent some time trying to recover; the first instincts of any pilot, and the use of ailerons are not required to recover from a spin, erect or inverted.

Here again the history is interesting. From quite an early age I was quite certain only one E.28/39 had been built, serial No. W4041, and that is still displayed in the Science Museum in Kensington, west London.

By contrast the first rocket powered aircraft, the German Heinkel He.176 first flew at Peenemunde on the 20th June 1939 – the jet powered Heinkel He.178 came later! This first flew, from the Heinkel works airfield at Rostock-Marienehe, on Sunday the 27th August 1939 and in both cases the test pilot was Erich Warsitz . His son, Lutz Warsitz, has written a very full and detailed account in his book The First Jet Pilot which I can highly recommend.

NOT A HAPPY HISTORY

The history of the companies and principal people involved in the development of the first jet engines and first jet propelled aircraft in the UK is not a happy one. It is well worth reading Frank Whittle: Invention of the Jet by Andrew Nahum. According to Robert Jackson in his book Britain’s Greatest Aircraft, in explaining why the Gloster Meteor was one of them, he gives some details concerning the Gloster E.28/39. He says that the engine speed was kept down to 16,500 rpm on the first flight in order to hold back the turbine inlet temperatures. Incredible, I think, that some internal combustion engines can now reach these speeds and indeed, at one point, in the Formula 1 racing world, engines once reached 20,000 rpm.

The main problem being with jets, at least for commercial use, that such high rotational speeds involve a lot of noise, or did. For example the Comet 4 used 8050rpm for take off and was very noisy, whereas a modern by-pass jet might be turning at anywhere between 8,000 and 15,000rpm, but, with the geared first stage fans turning much slower, the result is a huge reduction in noise. Unlike piston engines where RPM figures are usually viewed with considerable interest, with modern jet engines RPM is barely an issue, the thrust produced being the main consideration.

Incidentally, you might be interested to learn that in recent years large truck diesel engines have been refined to produce maximum torque roughly in a band between 1000 and 1600 rpm and depending on the model, usually with a peak torque in about a 300rpm range within these limits. Which is why the biggest trucks have had, for quite a long time, gearboxes with up to eighteen ratios, demanding a considerable degree of skill by the driver to use by ‘skip-shifting’ among the ratios available depending on the terrain and load carried – hence the introduction of semi-automatic gearboxes usually with an over-ride facility. The best of which are really quite fabulous to drive.

THE CHRONOLOGY

One aspect of aviation history that I now find quite fascinating, is the chronology. As a kid it was all so obvious – aeroplanes in WW2 had propellers – and the jets came later. To quote once again from Robert Jackson: “In August 1940, well before completion of the experimental E.28/39, George Carter, Chief Designer of the Gloster Aeroplane Company, had submitted a preliminary brochure to the Air Ministry, outlining his proposals for a turbojet-powered fighter. Realising that it would take too much time to develop a turbojet of sufficient thrust to power a single-engined fighter, Carter selected a twin-engine configuration, the design having a tricycle landing gear and high-mounted tailplane, with the engines housed in separate mid-mounted nacelles on low-set wings.” This of course resulted in the Gloster Meteor.

I think it is rather interesting to compare this design with the Westland Whirlwind designed by Teddy Petter which was of course the fastest aircraft then in production. Returning to Mr Jackson’s account: “In November 1940 the Air Ministry issued Specification F.9/40, written around this proposal, and design arrangements were finalised in the following month. On 7 February, 1941, Glosters received an order from the Ministry of Aircraft Production for twelve ‘Gloster Whittle aeroplanes’ to the F.9/40 specification. The planned production target was eighty airframes and 160 engines per month.”

To put this into perspective the first flight of the Avro Lancaster had occurred in the previous month on the 9th January. It seems to me, important to realise this, because although many in the RAF senior command positions were seemingly plotting to maximise heavy losses for the RAF in the bombing campaign, more enlightened people in the Ministry of Aircraft Production were also actively intent on developing this far more effective jet fighter. Both aspects happening, more or less, in parallel.

THE FIRST FLIGHT OF THE METEOR?

What does seem fairly certain is that the 5th prototype F9/40 (later to become the Meteor) also first flew here on the 5th March 1943. Possibly CRANWELL was selected due to its relatively closer proximity to Power Jets at Lutterworth in Leicestershire? When MORETON VALLANCE in GLOUCESTERSHIRE became available to Gloster all future development and test flying of the Meteor took place there. So, regarding jet aircraft the British started off almost exactly two years behind the Germans. The first German operational jet was the Messerschmitt Me-262 which first flew on the 18th July 1942, nine months before the F9/40. However, the British, (with Frank Whittle as the leading authority) were proving to be much better than the Germans at making their jet engines reliable enough for operational combat use and both types entered military service at virtually the same time – mid 1944. But, even then, as the famous test pilot Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown explained, the service life of the German jet engines was just 25 hours. The problem being, when ‘ordered’ to test fly them after WW2 ended, the Germans had destroyed the service histories so he had no idea if the example he was about to fly had, for example, 24hours and 59 minutes logged!

JUST A NOTE

The first squadron to receive Meteors was 616 based at RAF CULMHEAD in SOMERSET and as Robert Jackson points out; “It has often been stated, quite erroneously, that Germany’s Messerschmitt 262 was the world’s first operational jet fighter. In fact that honour fell to the British Gloster Meteor, which became fully operational a full two months before the first Me262 Staffel was formed in October 1944.” So, I suppose the next question is – which saw combat first? Probably the Me262 I suspect?

SPOTTERS NOTES

In 1977 the Auster J/1N Alpha G-AGXN, Taylorcraft Plus D G-AIXA, DH.82A Tiger Moth G-AOGR, Druine Condor G-AWST, Campbell Cricket (autogyro) G-AXRC and the Jodel DR.1050 Sicile G-AXSM were based here. (Or were they actually based at CRANFIELD NORTH?)

PERSONAL MEMORIES

This rather evocative sunset picture was taken in December 2006 after loading a Grob G.115 Tutor destined for repair at the Grob factory at Tuttenhausen-Mattsies in Bavaria, west of Munich. From CRANWELL I drove to Killinghome to catch a freighter across the North Sea.

PETER O'MALLEY

This comment was written on: 2017-08-06 19:23:18HELLO. MY GRANDFATHER, ROBERT HENRY RICHARDS, BASED IN SLEAFORD, WORKED FOR THE AIR MINISTRY UNTIL HE DIED OF T.B IN 1931. HE WAS AN INTELLIGENT MAN. THE FAMILY BELIEVE HE WAS CIVIL SERVICE. BUT WE HAVE NEVER BEEN ABLE TO FIND OUT WHAT HE DID. THEORY IS, THAT HE HELPED FORMULATE AND PUT TOGETHER THE FIRST PILOT TRAINING MANUALS. HE RAN A TEAM OF CLERICAL OFFICERS TO ACHIEVE THIS. BUT WE HAVE BEEN UNABLE TO DISCOVER MORE. YOUR ARTICLE AND INFORMATION FASCINATES ME, KNOWING MY GRANDFATHER WAS THERE AT THE START, IS WONDERFUL. THANKS. PETERO'MALLEY

Reply from Dick Flute:

Hi Peter, Many thanks for the kind remarks. I shall keep this posted as, although certainly a long shot, just possibly somebody can add more information. Best regards, Dick

Nicholas Pride

This comment was written on: 2018-10-05 15:14:32Hello Between about 1952 and 1957 my father was stationed at RAF Cranwell, and we lived on the camp in quarters. If anyone is interested, and can tell me where, I can provide a brief summary of my memories. Regards Nicholas Pride

Pete Theobald

This comment was written on: 2020-03-11 23:06:57I believe the spotter's notes at the bottom of the page to be correct, my late father bought G-AGXN in the early eighties and it was based out of Cranwell North during his ownership so I think it's highly likely that it was based there before he bought it.

Michael Holder

This comment was written on: 2020-05-05 11:56:49The College of Air Warfare moved to Cranwell in 1972 when RAF Manby closed down which included the Staff Nav Course and the Aero Systems Course for Navigators. I attended the Staff Nav Course in 1973; I completed it mid tour on 51 Sqn at Wyton. I was destined to become the NImrod R staff officer at 1 Gp in 1977.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide