Spilsby

SPILSBY: Military aerodrome

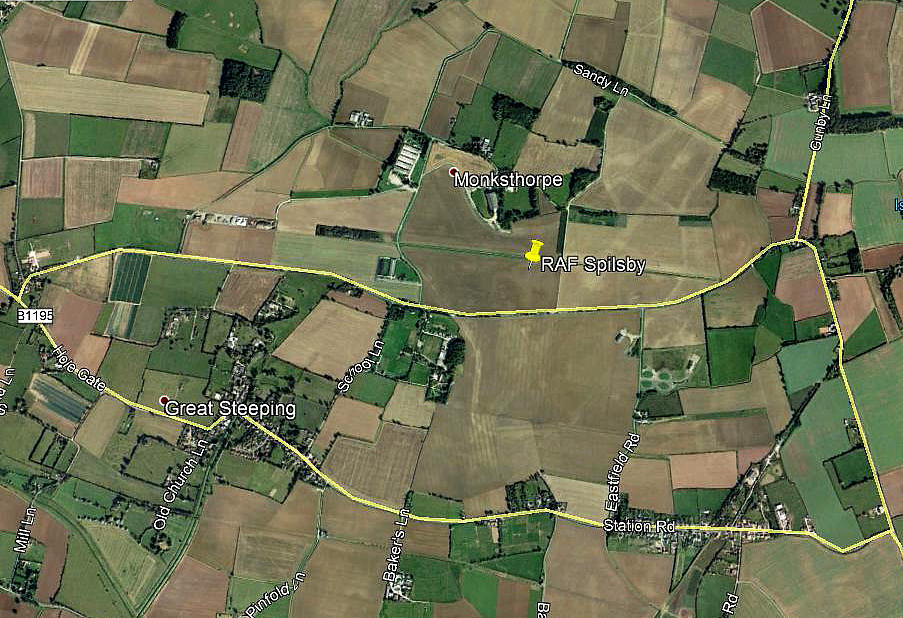

Note: This picture (2006) was obtained from Google Earth ©

The layout of this airfield can still be made out, even eighty years later. Evidence of the longest E/W runway can be clearly seen, as can in this dry period, the NE/SW runway. Plus, a dispersal area can be seen in the SE corner.

Military user: WW2: RAF Bomber Command 5 Group

44 (Rhodesia) & 207 Sqdns (Avro Lancasters)

Location: Surrounding and mainly S of Monks Thorpe plus roughly NE of Great Steeping villages, 3 nm E of Spilsby, 10nm WNW of Skegness

Period of operation: 1943 to 1958

Runways: 05/23 1280x46 hard 11/29 1829x46 hard

02/20 1829x46 hard

NOTES: Assuming the ‘official’ records are correct of course, or that Steve Willis and Barry Hollis hadn’t made a blunder with their records in their fabulous books, this aerodrome would appear to be unique in WW2 by having two 2000 yard runways.

AN ACCOUNT OF A BOMBING RAID

In his excellent book Bomber Crew John Sweetman tells the following story which is fairly typical of the type of extreme situation many bomber crews often faced. “…..Lancasters from 44 Squadron at RAF Spilsby, Lincolnshire, formed part of 226 bombers to take part in a daylight raid on a synthetic oil plant at Homberg. After an ‘uneventful’ outward journey 10/10ths cloud was found over the target and Pathfinder aircraft therefore released sky markers. The Germans, however, put up a ‘very accurrate’ box barrage, which damaged eleven of the thirty-seven Spilsby bombers. The aircraft of Flying Officer Jack Hawarth, ‘a quiet retiring Rhodesian, well liked by all who knew him’, was hit by shell bursts which shook the machine and ‘very nearly deafened the crew’.

According to the post-operational summary, when the situation had calmed down they saw to their horror that the pilot had been ‘seriously injured and that the greater part of the instrument panel was destroyed’. Fatally wounded, Hawarth died soon after, which left the crew ‘in a very critical condition’. The others did not know that the flight engineer, Sergeant M. F. Seiler, had been shot in the leg as he ‘quietly’ carried on his duties. The bomb aimer, Flight Sergeant G. W. Walters, took the controls to find that the airspeed indicator and altimeter were still functioning, although no other instrument was working. One engine was dead, and Walters had little flying training, but he offered to try and get back to England so that they could bale out over friendly territory. With his limited skills, he could not guarantee to land the aircraft. Including the rear gunner, Sergeant A. W. McAllister, who had hacked his way out of his damaged turret, the others agreed that Walters should go on.”

What followed though was I think, quite remarkable and totally reinforces the exceptional bond bomber crews invariably formed. “Flying above the cloud, he relied on the few instruments still left, as the wireless operator sent out: ‘Captain injured. Crew baling out over England.’ Walters and Seiler did eventually get the Lancaster over the coast, aided by Sergeant B. J. Saunders’ ‘excellent navigation’, and they duly prepared to bale out. Although convinced that Hawarth, the pilot, was dead, they nevertheless sent him out on a static line, before leaving the bomber themselves. Five of the crew landed safely; sadly, the wounded Seiler did not. Walters had been the last to jump and ‘richly deserved’ the Conspicious Gallantry Medal he received.”

My note: I think this illustrates very well the well founded fear RAF aircrew had of baling out over enemy territory. There had been instances of bomber aircrew baling out over Germany only to find themselves surrounded by very hostile locals intent on lynching them or despatching them by other means. Very often they were saved by German soldiers or policeman who, although heavily outnumbered, rather courageously I would say, insisted the airmen had to be treated as prisoners of war and treated humanely. The fact that civilians often behaved in such a way surely indicates the terrifying effect the ever increasing severity of the bombing campaign was having. It might also indicate that the German civilian population were mostly unaware of the Blitz camapaign the Luftwaffe had inflicted on Britain, for which they were now 'reaping the retalliation'.

THE 'WRITING WAS ON THE WALL'

As said elsewhere the ‘writing was on the wall’ for the Nazi regime as early as the start of 1943 with the devastatig raid on Hamburg – if not before. Much has been written after the war of the sheer barbarity of the bombing campaign by the RAF. (Oddly the Americans who had by 1944 joined in, don’t seem to share this blame, and they had not had their cities blitzed by the Germans). It seems clear this shallow material is written by people who have utterly failed to understand the situation by not taking the time and trouble to research the history even at a superficial level. Yes, it was barbarous, but only because we were fighting one of the most extreme regimes utterly devoted to ruthless death and destruction, (including their own population), on a scale the world has rarely ever seen. And, it tends to be forgotten that the UK was soon to face the horrendous prospect of the V.1 and V.2 terror weapons.

ANOTHER POINT TO MAKE

As explained elsewhere it has been a deliberate intention in this ‘Guide ’to often illustrate bigger points in the notes on airfields now almost forgotten by ‘the general public’. I trust that most if not all will agree that SPILSBY hardly ranks as a significant WW2 RAF bomber station? In this case I have included an account of how fraught with danger even the take-off run was for bomber crews. Here again I have John Sweetman and his book Bomber Crew to thank.

“A 207 Squadron pilot on his first operation as an aircraft captain failed to get airborne in spectacular and tragic circumstances. Australian Flying Officer A. T. Loveless was carrying fourteen 1000lb. bombs in his Lancaster. About one-third of the way down the runway, the aircraft swung violently to port – the pilot later reported that he ‘felt as if something had given way, causing the aircraft to develop a will of its own and leaving him without proper control of it’. Careering off the runway, the Lancaster sped across the grass, with Loveless striving to regain control. Section Officer Joyce Brotherton, the Intelligance Officer, reported that it ‘hurled itself upon the empty Halifaxes, at the same time flattening a small Nissen hut. By a miracle, no one was killed or even injured and the crew leapt out and ran for their lives’. All except the bomb aimer who was trapped. Realising his predicament, Loveless rushed back to free him just before an enormous explosion occurred; almost certainly from the petrol tanks.

‘A huge column of smoke rose into the air, while flames continued to spread.’ None of this was near the runway, so waiting bombers were free to take-off. The Lancaster, though, was a complete write-off.”

“It very nearly accounted for Flying Officer J. Downing, like Loveless on his first solo operation, in one of the following Lancasters. The Intelligence Officer explained: ‘When he was about halfway down the runway, an explosion which made the first one pale into insignificance rent the air. The heat had caused the main bomb load to go off. Smoke, fire and debris were hurled into the air and pieces of flaming wreckage were scattered far and wide.’ Some fell in the path of Downing’s aircraft, which was now going too fast to abort. 'Spectators, most of whom were lying on the ground by this time, held their breath while the aircraft passed through the flaming debris – unharmed.’ However, with sharp pieces of metal strewn across the runway, the remaining six Lancasters were told not to take off.” The explosion also caused considerable damage to important buildings on the airfield such as the squadron offices, the Control Room and Met. Office etc.

By now I suspect even my best friends will be asking themselves, “I’ll bet the devious old sod has another point to make? Why else does he go on at such length here?” And of course they are correct. The two pilots featured in both these stories were not British. One was Rhodesian, the other Australian. It nigh on drives me mad today when time and time again the RAF air victory in WW2 is so often described as being a British affair. Our part was largely a British Empire contribution and the immense sacrifice of huge numbers coming from the Dominions etc cannot be simplistically described as being British. Of equal importance was the part played by ‘our’ airmen, all 'foreign' who had made their way across from the occupied countries in Europe and last but not least the few incredibly brave Americans who had managed to enlist, even though faced with severe retribution by the US government if discovered - before the USA joined in.

Perhaps I’m wrong? The importance of their contribution is certainly recognised by serious historians writing accounts of World War Two, but I fail to hear the point emphasised at air shows where, for example, the ‘Battle of Britain Memorial Flight’ appears.

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide