The first non-stop trans-Atlantic flight

THE VERY FIRST NON-STOP TRANS-ATLANTIC FLIGHT

Note: The U.S. Navy had already crossed the Atlantic, via the Azores to land in Plymouth previously, employing four aircraft and dozens of naval ships to mark the way. What marked this flight out was that it was non-stop, and, taking less than 72 hours was eligible for the Daily Mail prize.

There was a lot going on during this period. About one month later, after Alcock and Brown had made their non-stop flight in an aircraft, the British airship R34 made the first double crossing of the Atlantic.

Picture galleries from the ALCOCK & BROWN hotel in Clifden and the memorial site

The Alcock & Brown hotel in Clifden, which has a bar and restaurant area dedicated to the exploits of these two intrepid airmen, was so named because it opened in 1969, on the fiftieth anniversary of the flight. Highly recommended for a visit by people, such as myself, interested in this subject. The site of the landing at Derrigimlagh, near to the Marconi transatlantic telegraph station has two memorials, neither of which are on the actual site where the landing took place. However, adjacent to the road and the car park, there is a visitors information facility.

SOME BACKGROUND INFORMATION

This flight by Alcock and Brown is often portrayed as being conducted by two dare-devil aviators. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact Alcock was trained and flew in the RNAS (Royal Naval Air Service) and Brown was trained and flew in the RFC (Royal Flying Corps). And, both took their flying duties very seriously. John Alcock (born 1892) gained his pilots license in November 1912 and was a regular competitor at events held at Hendon aerodrome.

Oddly enough, they both became prisoners of war. In Alcock's case he was imprisoned by the Turkish authorities after suffering engine failure over the Gulf of Xeros. For Brown he was shot down over Germany. But both remained determined to continue flying. Arthur Whitten Brown, born 1886, was, after WW1 determined to develop his navigational skills. Both Alcock and Brown were dedicated to becoming highly proficient aviators.

In April 1913 the Daily Mail newspaper offered a £10,000 prize for the first flight from the USA, Canada or Newfoundland to reach Ireland or the British mainland in under 72 hours. During WW1 this was offer was suspended, but after the war ended, the offer was re-instated, still at £10,000 - roughly half a million pounds today.

The Vickers company, after WW1, had also realised that a modified version of their Vimy IV bomber, was a highly suitable type for attempting this feat. And, in fairly short order Alcock and Brown were selected to crew their entrant.

AND MORE PICTURES

OTHERS WERE TAKING PART

When the Vimy took off at 1.45pm from Lester's Field, St John's, Newfoundland, (then not part of Canada incidentally), on the 14th of June 1919, and, very heavily laden with fuel, the Vimy only just managed to clear some trees near the 'airfield'.

It has to be remembered that they were not alone. Indeed, a team from the Handley Page company were also keen to secure this record flight. Vickers had employed Admiral Mark Kerr to ensure that the aircraft was thoroughly checked, and Rolls-Royce had people there to make certain that the engines were in 'tip-top' condition. As said, this flight was by no means an attempt by a couple of 'dare-devils'.

This said, nobody involved was under the illusion that this flight could ever be easy. Far from it. Indeed, centuries of experience from ships crossing the Atlantic gave Alcock and Brown a pretty good idea of what to expect. But of course, given their expertise and experience, both must have felt they stood a good chance, and, if they succeeded their claim to fame would be enormous and everlasting. That in itself has always been an allure for those brave enough, and young enough, to attempt going into the unknown.

THE FLIGHT ITSELF

There are many accounts of the flight itself, all full of drama and hair-raising escapades, and they are mostly pretty accurate it would appear, widely available and therefore need not be repeated in this article.

The bare facts appear to be that the flight lasted fourteen and a half hours, (Alcock & Brown claimed 15hrs 57mins), and covered 1.890 miles at altitudes ranging from sea level to 12, 000ft at an average speed of 115mph. A simple calculation shows that they actually averaged 118mph - so why the discrepancy?

This is easy enough to explain as the indicated airspeed in an aeroplane usually bears little relationship to the speed over the ground - or sea - which obviously depends on the direction and speed of the winds affecting the flight. As the prevailing winds over the north Atlantic, at most levels normally at least are easterly, it follows that the Vimy was assisted by a tailwind most if not all of the way. Which also explains why eastbound flights by modern airliners, using the jetstream winds at high altiude are invariably if not always, far quicker than westbound flights, often by an hour or even two.

AND EVEN MORE PICTURES

Note: These pictures were taken at the visitors information centre, adjacent to the car park. One has to wonder, regarding the first picture, considering that the Daily Mail had offered the prize, just how the Daily Mirror managed to present this front page?

THE ARRIVAL ON BRITISH SOIL

There are two aspects here. The first is that many accounts omit to mention that in 1919, this part of the Republic of Ireland was then still part of the United Kingdom, until independence was agreed about two years later. The second aspect is that Alcock and Brown deliberately selected a landing ground near to the Marconi transatlantic telegraph station at Derrigimlagh SSW of Clifden so that news of their success could be sent around the world, and especially to the Daily Mail and Vickers.

The fact that they eventually made landfall so close to this site speaks volumes for the navigational expertise displayed by Arthur Whitten Brown. I always reckoned that the really skilful part of a flight was the navigation, radio communication etc, rather than 'handle-bar' management. At it turned out Arthur Brown had made a incredibly fine job of the navigation and the Vimy arrived on the Irish coast not very far from the Marconi site. Not only that, but Brown, having established his bearings exactly in poor weather, directed Alcock to fly south to their diversion point.

Note: This first picture was obtained from Google Earth ©. In October 2020 Mr David Hill kindly sent me this picture of the cover of the celebratory lunch menu held by the Daily Mail at the Savoy hotel. This being from the Chronicle of Aviation published by J L International Publishing in 1992. If you look closely Alcock had signed the copy.

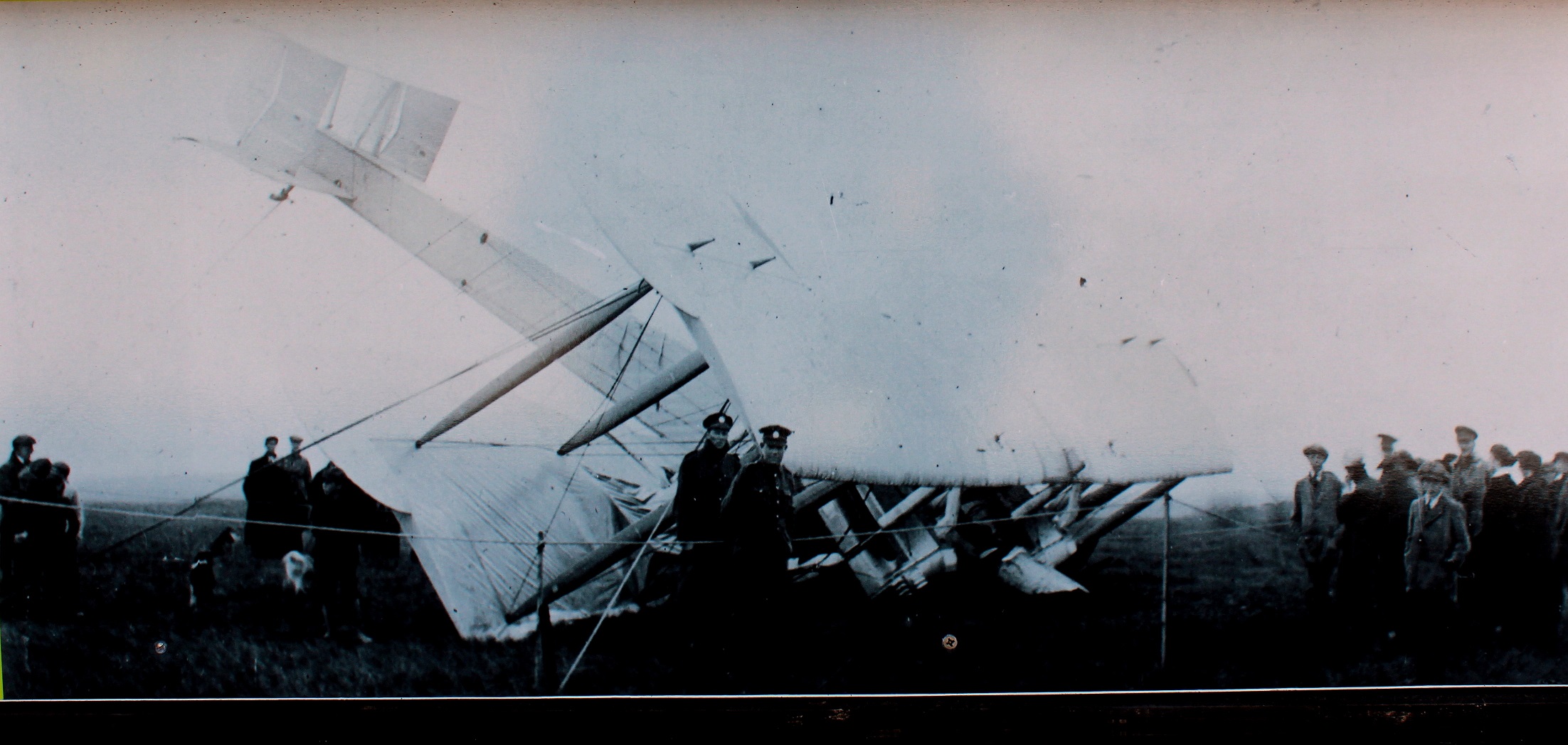

THIS LANDING WAS NOT ACCIDENTAL

This was not, as is commonly portayed, an ad hoc crash landing site. In fact, the landing site selected appeared, from the air, to be quite suitable for a landing near to the Marconi transatlantic telegraph station and a lightly laden Vimy could land easily on most unprepared fields and similar pastures etc. Unknown to Alcock and Brown was that this apparently suitable site, seen from the air as looking like a pasture or similar, was in fact a soft peat bog. After a fairly short run the undercarriage sank in and the Vimy tipped over on its nose.

With fuel dripping from severed fuel pipes, the two airmen, apparently unhurt, beat a hasty retreat. Fortunately the Vimy did not catch fire, and was salvaged. It was later on display for many years in the Science Musuem in Kensington, London. In 2006 it was donated to the Brooklands Museum in Surrey. A replica now takes its place in the Science Museum.

If the weather had proved acceptable, the original plan was to land at an aerodrome near to central London.

KNIGHTED

Shortly after completing their flight John Alcock and Arthur Brown were knighted by King George V at Windsor Castle. Sadly, John Alcock had little time to appreciate his honour as he died in a crash on the 18th December 1919, near Rouen in France, when delivering a new Vickers Viking amphibian to the Paris Airshow. Arthur Brown died on the 4th October 1948.