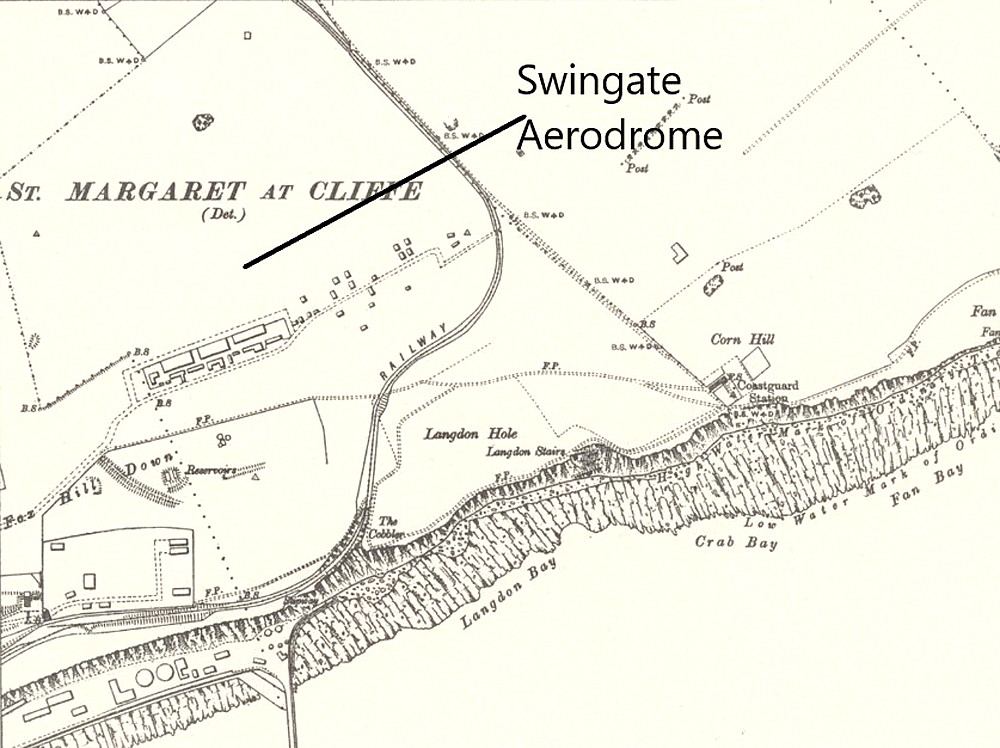

Swingate Down

SWINGATE DOWN: Military aerodrome later temporary civil aerodrome (in WW1 aka DOVER, and St MARGARET’S AERODROME)

Note: This picture was obtained from Google Earth ©

Military users: WW1: RFC/RAF/RNAS Transit Station for flights to and from France

RFC/RAF Training Squadron Station and Training Depot Station

3 Wing (RNAS) 1915 (Flying ?)

Home Defence Flight Station: 49 Sqdn (Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c & R.E.7s)

50 Sqdn (Armstrong-Whitworth F.K.8s, Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2s, B.E.12s & S.E.5a, Bristol M.1s, Sopwith Pups, Sopwith Camels and Vickers E.S.1s)

20 Reserve Sqdn

RNAS No.1 and No.4 Wings (Sopwith Pups)

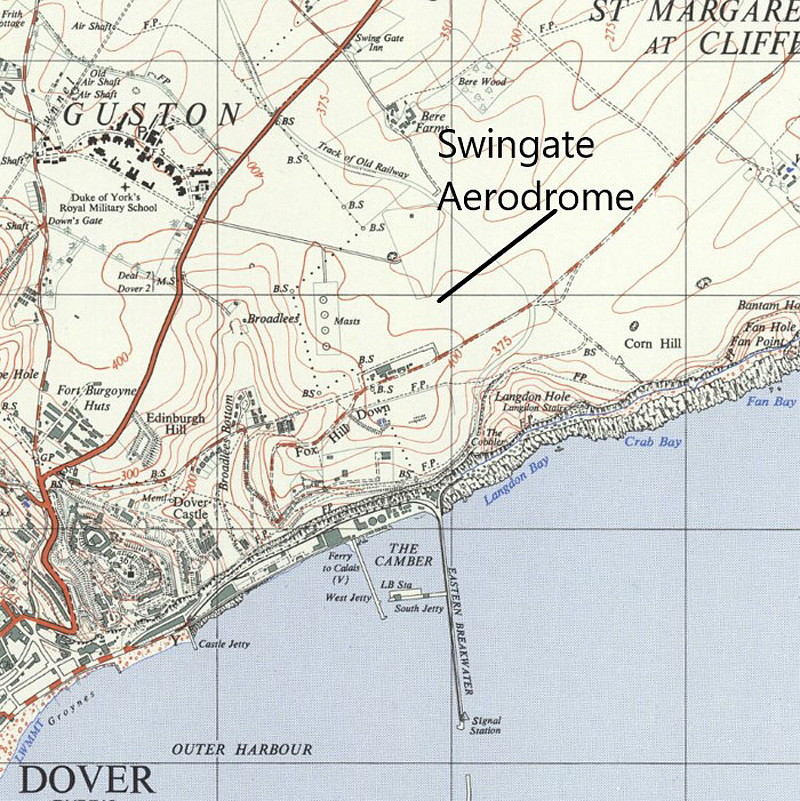

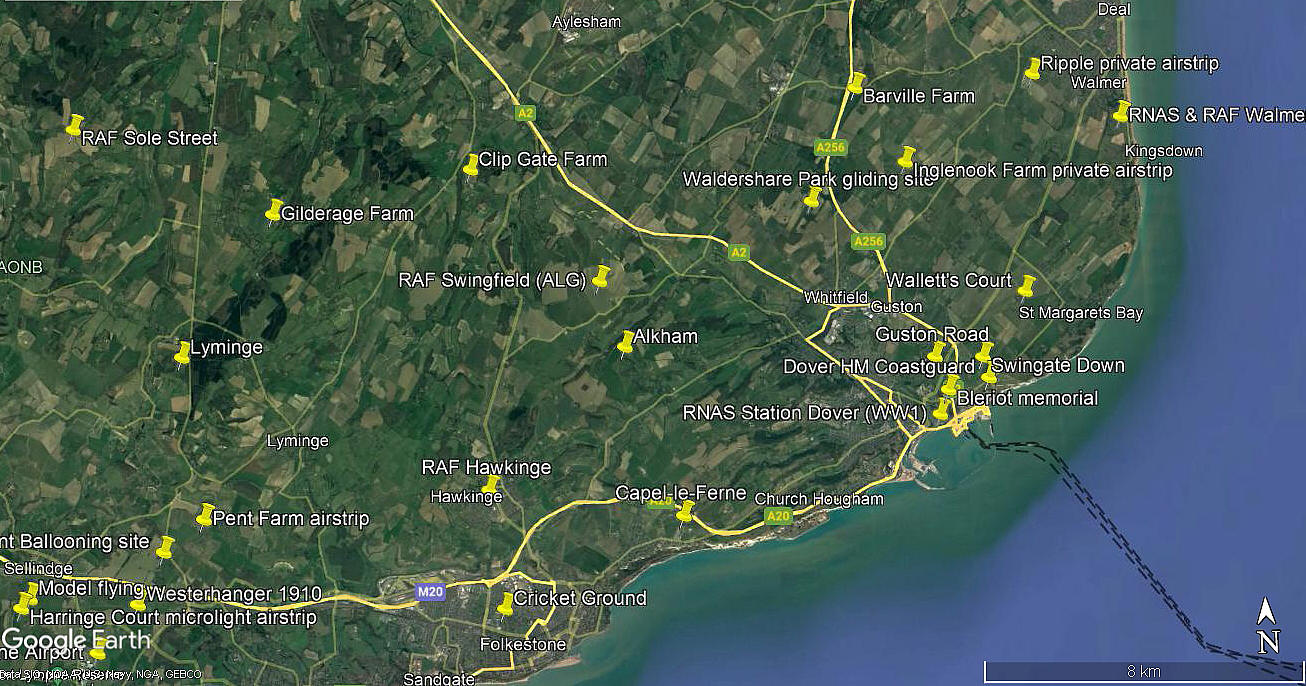

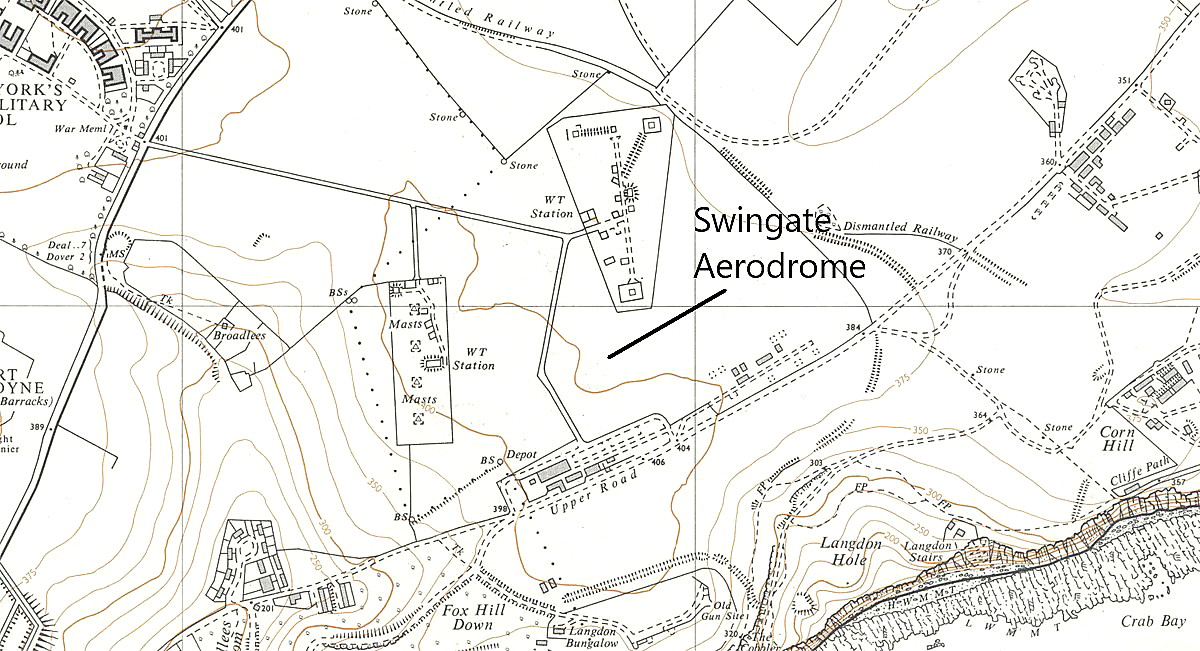

Location: Near the A258 roughly 1nm NE of Dover

Period of operation: Military: 1914 to 1920 Civil: 1929 to 1932 only?

NOTES: The first ‘mass exodus’ of RFC aircraft to transit to France in WW1 took place here between the 13th and 15th of August 1914. Some say the ‘mass’ fly out took place only on the 13th and I now believe this is probably correct? This has also been described ‘as a continuous stream’. If fact it was just sixty three aircraft of 2, 3, 4 and 5 Squadrons who assembled here before departing for Amiens. And it appears, they all made it, at least for the Channel crossing. I can only try to imagine how those very brave pilots felt as they ‘coasted out’ in those days so long ago. The aircraft types are said to be BE.2a, Avro 504, Farman and Blériot. They were accompanied by two dirigibles, Delta and Silver Queen. Amiens was a regrouping point, the final destination being Mauberge about ten miles behind the lines of the British Expeditionary Force.

According to Patrick Bishop in his book Wings No.1 Squadron was in the process of “switching from balloons to aeroplanes” and, “Two more – 6 and 7 – were being assembled.” He then states that: “Two squadrons – Nos. 2 and 4 -were equipped with BE2s. The rest flew with the ill-assorted array of machines acquired in the first rush of growth.”

He goes on to say: “The first great test was to get to the battlefield. Between them and the plains of northern France, from where they would operate, lay the English Channel, still a formidable obstacle. When the order came to move to a temporary encampment at Swingate on the cliffs above Dover, the squadrons were scattered around the country. No.2 under Burke was in Montrose on the east coast of Scotland and got there without mishap."

AIRCRAFT FOR RECONNAISSANCE

Almost none, (or should I say very few?), of the senior military staff in the three major combatant nations had by that time fully appreciated the use of the aeroplane. Which does seem quite extraordinary as balloons especially and even man-carrying kites had been largely accepted as being useful for artillery spotting and general reconnaissance. The balloon of course being by far the preferred option in France and Great Britain.

It is claimed the German military had the largest air force when war was declared – 246 aircraft and seven airships. France had 160 aircraft and fifteen airships. The RFC declared 189 aircraft but it seems that many were worn out and broken, or in use at the Central Flying School.

Hence just sixty three departed for combat duties. And indeed, some aircraft from the Central Flying School at NETHERAVON were allocated to fly to France. In fact one suffered the first fatal RFC accident of WW1 shortly after taking off from NETHERAVON for Dover with an engine failure. Lieutenant Robert Skene and Air Mechanic R K Barlow, of 3 Squadron perished.

Patrick Bishop takes up the story: “Other mishaps complicated the departure. No.4 Squadron suffered two non-fatal crashes on the way to Dover. No.5 Squadron was held up in Gosport and would have to follow later. But at 6.25 on the morning of 13 August the aircraft that had made it began, on schedule, to take off. First away was Lieutenant Hubert Harvey-Kelly, of 2 Squadron, at the controls of a BE2a.” It can only be wondered at as to how most of those pilots felt contemplating crossing the Channel. Many of the pilots of 2 Squadron, having already crossed far more dangerous the Irish Sea, probably took it in their stride? “He (my note: Harvey-Kelley) was followed by Burke, who led his men over the French coast, then turned south towards the mouth of the Somme, which pointed them towards their destination, Amiens aerodrome. Harvey-Kelly was determined to touch down first and broke formation to cut across country, arriving at 8.20.”

“The pilots of 2 Squadron all landed safely and by nightfall there were forty-nine aircraft on the base. The local people – who had been in some doubt as to whether the British would come to their aid – gave them an ecstatic welcome.” Nothing like this would or could happen today I expect, unless arranged as a PR exercise, heavily managed. Indeed, modern military pilots would probably have very little if any contact with the local people they are ostensibly “on station” to defend?

NO MARKINGS

It might be of interest to learn that these first RFC aircraft had no distinct markings on them. This might appear rather odd as the European and British military had always set much store of having highly distinctive military uniforms for centuries? It seems the Germans had painted black crosses on the upper surfaces of their machines and the French had painted roundels on theirs. Once the problem of ‘misidentification’ had been recognised it appears the British painted Union flags onto their wings and the sides of their fuselages but these were easily mistaken for the German crosses. So, these were replaced by roundels with a red centre, surrounded by white and blue concentric circles, the opposite of French roundels. A superbly practical solution to both clearly identify friendly aircraft and distinguish between the French and British machines.

'FRIENDLY FIRE'

During the initial stages of aerial operations in WW1 the pilots on both sides faced the problem of ‘friendly-fire’ as it was later called. As Patrick Bishop describes in his book Wings: “The British stand at Mons gave way to a long retreat and the RFC fell back with them, setting up makeshift camps at Le Cateau-Cambresis, then St Quentin, then Compiègne, sleeping wherever they stopped, sometimes in a hotel bed, more often in a hayloft or even in the open under the wings of their aircraft. Despite the chaos they managed to maintain a flow of reports to headquarters. The main hazards came from the vagaries of their machines and from ground fire, which rose to greet them indiscriminately no matter which side of the lines they were over."

This was a hazard which went on until at least the end of WW2 and still exists today. During this period, in any theatre of war, both Army and Navy gunners would happily try to shoot down any aircraft. Needless to say, no records exist regarding how many aircraft on their ‘own side’ they managed to down. "The French troops were much the same: “ - and in the early days the crews were as much as risk from friend as they were from foe.”

A 'D-DAY' NOTE

This very real risk was of course the reason why Allied forces aircraft in the D-Day invasions were painted with broad black and white stripes. It will never be known just how effective this innovation was, because when seen from many angles, these stripes could not be seen, especially when the aircraft appeared in silhouette against the sun. Indeed there are records of at least one British naval ship deliberately stationed to shoot down RAF aircraft returning across the Channel!

THE AMOUNT OF AIRCRAFT CROSSING THE CHANNEL

It is today surely quite impossible to imagine the sheer quantity of aircraft being ferried across the Channel towards the end of WW1? For example I’ll quote from Ron Smith in his Volume 5 British Built Aircraft regarding comments made by M Flaudin, head of the Allied Air Board and printed in the American magazine Flying in September 1917: “The average life of an aeroplane at the battlefront is not more than two months. To keep 5,000 aircraft in active commission for one year it is necessary to furnish 30,000. Each machine in the period of it’s activity will use at least two motors, so that 60,000 motors will be required.”

A MONUMENT NEEDED

I think that a major monument should be erected to all aircrew who died in both World Wars during training. Their loss of life is no less worthy than those who died in combat? They died serving exactly the same cause as those who saw combat. The military of course try to hide the figures because they really are a national disgrace. Ron Smith quotes; “A question in Parliament during the 1918 Air Estimates debate revealed that during 1917 more men were lost at the training schools than were lost flying on all fronts.” This said, those that survived the training programme had a very bleak future to contemplate. In April 1917 for example the average life-expectancy for a RFC pilot on operations was just 17.5 flying hours! It is now reckoned that of the 14,166 pilots who lost their lives in WW1 over half were killed in training.

50 SQUADRON

50 Squadron were formed here in WW1 and flew a considerable range of different types, which was a ‘tradition’ they kept up until disbanded at WADDINGTON in 1984 when flying Vulcan air-to-air tankers. At the close of WW1 the Commanding Officer was Arthur Harris who went on to head up Bomber Command in WW2. Incidentally, 50 Squadron in WW1 had Flights based at various other Kent airfields.

AIRCRAFT REPAIR

The 6 Wing Aircraft Repair Station is listed as being in DOVER. Probably here I would now think? It seems they repaired nine Sopwith Pups, three Sopwith Camels and a Sopwith 1½ Strutter. Plus an Avro 504, a BE2C and both a DH4 and DH5. Doesn’t seem much of a result for setting up such a facility? But of course it might well have been just a basic hangar with fairly minimal equipment and facilites for the task?

UNRELIABLE ENGINES

The Britsh were, by and large, not always competent at producing reliable aero engines despite our industrial heritage. One attempt in 1918 to produce a standard engine was the ABC Dragonfly, a programme which was a disaster. It achieved a typical engine life of only two and a half hours before failure! But of course those in charge of procurement were often utterly incompetent fools and, it can well be argued, just such people still occupy similar positions today. Or is this being far too cynical and unfair?

CUSTOMS APPROVED

Almost certainly this aerodrome was listed as being ‘Customs Approved’ for international flights in 1919? The first was HOUNSLOW HEATH followed by CRICKLEWOOD (both in LONDON), LYMPNE and DOVER in KENT, (the latter surely SWINGATE DOWN?), and HADLEIGH in SUFFOLK. To date I have discovered nothing to indicate that any attempt to build an ‘airport’ at HADLEIGH was ever commenced and it does seem a strange choice.

POSSIBLE FLYING VENUES?

From a variety of sources it does appear this site was used by the Cobham Tours.

SWINGATE aerodrome was intended to be the 51st venue (13th August 1929) for Sir Alan Cobham’s Municipal Aerodrome Campaign. As it turned out it was the 53rd venue.This Tour started in May and ended in October with one hundred and seven venues planned to be visited. Mostly in England this Tour included two venues in Wales and eight in Scotland. Without much if any doubt this Tour resulted in several aerodromes/regional airports being commissioned. But, due to a couple of accidents and other problems, Cobham managed to visit around 96 venues. Still a magnificent achievement.

What seems very interesting, and I have yet to find any proof, is that SWINGATE appears to have been an operational aerodrome when this visit occurred? It needs to be remembered that just a suitable field was needed, and the previous WW1 airfield would, presumably, have been ideal?

The aircraft Cobham used for this Tour was the DH61 'Giant Moth' G-AAEV named 'Youth of Britain'. The punishing schedule he set himself seems astonishing today. See STOCKTON-on-TEES for more information. Better still read his memoirs in 'A Time to Fly'.

Venue, (24th May 1932) for Sir Alan Cobham’s National Aviation Day UK Display Tour?

A MICHEAL T HOLDER GALLERY

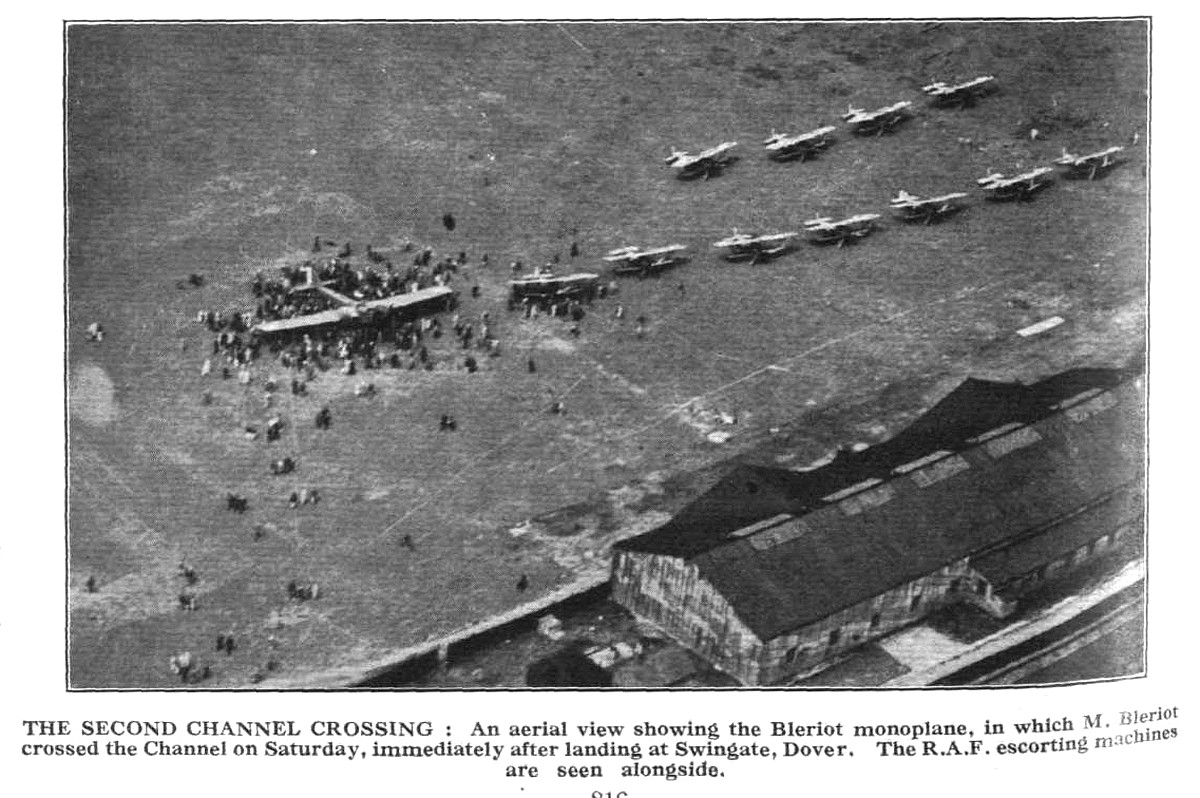

Note: The second picture is of a celebration of Blériots first Channel crossing. The aeroplane was a fudge as the original could not climb high enough to land here! The third item is an article published in the Dover Express on the 9th August 1929.

Note: The seventh item, an area view, was added from my Google Earth © database.

peter Smith

This comment was written on: 2020-11-13 13:24:20Hi I am researching my wifes grandfathers time in the RNAS. He volunteered in November 1914 and from his records I have found that he was stationed at "Dover Leap" I believe this to have been Swingate Airfield but I have not been able to find any information to verify this. The term is used on an official document so I assume that it would have been a recognised place during WW1. The "Dover Historian" pointed me in the direction of Swingate so I wonder if that information could be verified.

Dick Flute

This comment was written on: 2020-11-13 18:31:02Hi Peter, I am not familiar with this name. However, and it is purely a guess, the RNAS had a small flying boat station on the east side of the harbour in WW1. Could that have been known as 'Dover Leap' I wonder? Best regards, Dick

We'd love to hear from you, so please scroll down to leave a comment!

Leave a comment ...

Copyright (c) UK Airfield Guide